Thanks to smartphones, pretending to be somebody online is effortless. All it takes is a couple of photos, a different user name, and voila — you’re in business. But it takes extraordinary planning and manipulation to be a successful catfish. Finding photos for profile and feed images creates new email addresses for fake Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat accounts.

Writer: Jibi Moses

Catfishing is a growing problem online, with more and more people falling victim to scams involving false identities. According to recent statistics, 41% of U.S. online adults said they had been catfished at some point – an increase of 33% since 2018. In Britain alone, over 200,000 people may have been catfished on dating apps in 2019, while romance fraud grew by 50% between 2018 and 2019 in Australia.

In North America, 29% of all catfishing incidents occur worldwide. In comparison, women are 63.2 % more likely to be targeted than men, according to one survey, which found that 45 per cent of men and 43 per cent of women reported being approached by someone with false online identities. A study by Eharmony revealed that 50 % of participants encountered fake profiles when using dating websites or apps. In comparison, another website reported almost 80 % of users were involved in conversations with scammers at some point.

Romance scams cost consumers 201 million dollars last year, only within the United States. In contrast, the average loss per person was 11,145 pounds for UK victims and 24,438 Canadian Dollars for Canada Victims, respectively. The FBI also recorded 20 thousand complaints related to Romance Scams, including Catfishing Scams reaching a record high in 2020, where 85 per cent of cases involved False Photographs used in Fake Profiles & the 25-34 age group most likely get targeted, accounting for 24 per cent out of overall victims list. Finally, 35% of Online Dating Users faced similar scamming attempts, and 61% of US daters encountered the same issue during the pandemic this year.

What is Catfishing?

Catfishing creates a false identity and interacts with someone for a specific purpose, usually to “lure” them into a relationship. This can include mild flirting to years-long partnerships. The catch? These people have never and will never meet in real life, although they can spend an hour a day communicating with someone.

Thanks to smartphones, pretending to be somebody online is effortless. All it takes is a couple of photos, a different user name, and voila — you’re in business. But it takes extraordinary planning and manipulation to be a successful catfish. Finding photos for both profile and feed images, creating new email addresses for fake Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat accounts — the lengths people will go to to keep up the charade are mind-boggling. They must also stay “in character” when messaging so they don’t slip up. In extreme cases, catfishing can also lead to severe harm and even death, as in the recent case of a family in California in 2022.

How Catfishing Works

You may wonder why a person would believe a catfish and continue an internet-only relationship. For catfishing to work, the victim must also want to believe that the catfish is real — whether because of loneliness, desire, friendship, or more.

This isn’t to say that the victim is at fault. It’s just that the catfish knowingly uses flattery and emotional manipulation to kickstart a connection and then nurtures it steadily. And because catfish isn’t who they say they are, they’ll constantly come up with excuses for not meeting in real life or via video chat. If they did, they would instantly give up their real identity. Common excuses include:

- “My phone is broken.”

- “I’m shy.”

- “My mom’s home.”

- “The internet’s acting wonky.”

- “ Am broke”.

Of course, any of these reasons could be valid for a real-life friend, but when they happen every time communication is attempted, it’s a sign that something may be wrong.

Why People Catfish

There are many different reasons why a person would pursue a fake relationship, ranging from boredom to harmful ulterior motives.

Low self-esteem: Some individuals may lack the confidence to interact with people as their real selves. They can live out their romantic fantasies by creating more attractive versions of themselves with fake photos.

Jokes: Sadly, catfishing can happen just because a person is bored and wants attention. It may also be a very targeted form of cyberbullying among kids, especially as a way to pick on less social teens and tweens.

Revenge: Former romantic partners may turn to catfishing to get back at their ex. Here, the catfish gets satisfaction knowing that their ex is emotionally invested in a fake relationship, which will inevitably fail or be revealed.

Fraud: Some catfish will start relationships for the sole purpose of getting money out of somebody, whether through fabricated sob stories, extortion, or other deceptive means.

Grooming: When an adult catfishes a child for eventual abuse, it’s called grooming. It’s a crime whether the predator pretends to be a child or not, however.

How Kids Are Especially Vulnerable To Catfishing

Kids don’t always assume the worst of people, especially when someone is being nice to them online. For victims of bullying-type catfish, there’s often a genuine desire to fit in or be loved. A shy teen or tween who thinks they’re being messaged by the most popular kid in school may want nothing more than for that to be true. Their critical thinking skills and scepticism overlook warning signs and missing information in the hopes that it may happen, just like in the movies. Sadly, it’s often just mean-spirited classmates preying on their vulnerability.

As for adults who pretend to be kids, it’s manipulation and abuse, plain and simple. Predators are known to target lonely kids or children from less stable households. They may pretend to be a kid at first or simply lie about their age. The adult slowly grooms their victim by paying them compliments, listening to them, or buying them gifts. This may pave the way for an eventual in-person assault. Though it doesn’t have to — a child and a predator never have to meet for abuse to occur.

Catfishing Warning Signs to Look Out For

Not sharing personal info.

Creating all aspects of a fake person’s life from scratch takes a lot of work, so, unsurprisingly, a catfish may not have thought of everything. Noticeable gaps could include details about their family, what classes they’re taking (if a kid), or even what part of a city they live in.

Only text chats

As we mentioned, catfish can never expose their real identity, meaning that real-time video chatting or meeting up in person is definitely off the table. To compensate for this, they’ll pour lots of energy into text messaging and DMing.

Few candid photos

A catfish usually has to have at least a few photos of the person they’re pretending to be. But recent, updated photos — like a selfie with the giraffes if you said you were going to the zoo that day — aren’t an option for a catfish.

Asking for or giving you things

For the catfish looking to take advantage of people for monetary gain, they’ll begin by asking for small favours or gifts. It may progress to online gift cards, Venmo requests, and more. The same may also be true in reverse: a catfish may shower a victim with presents to win them over.

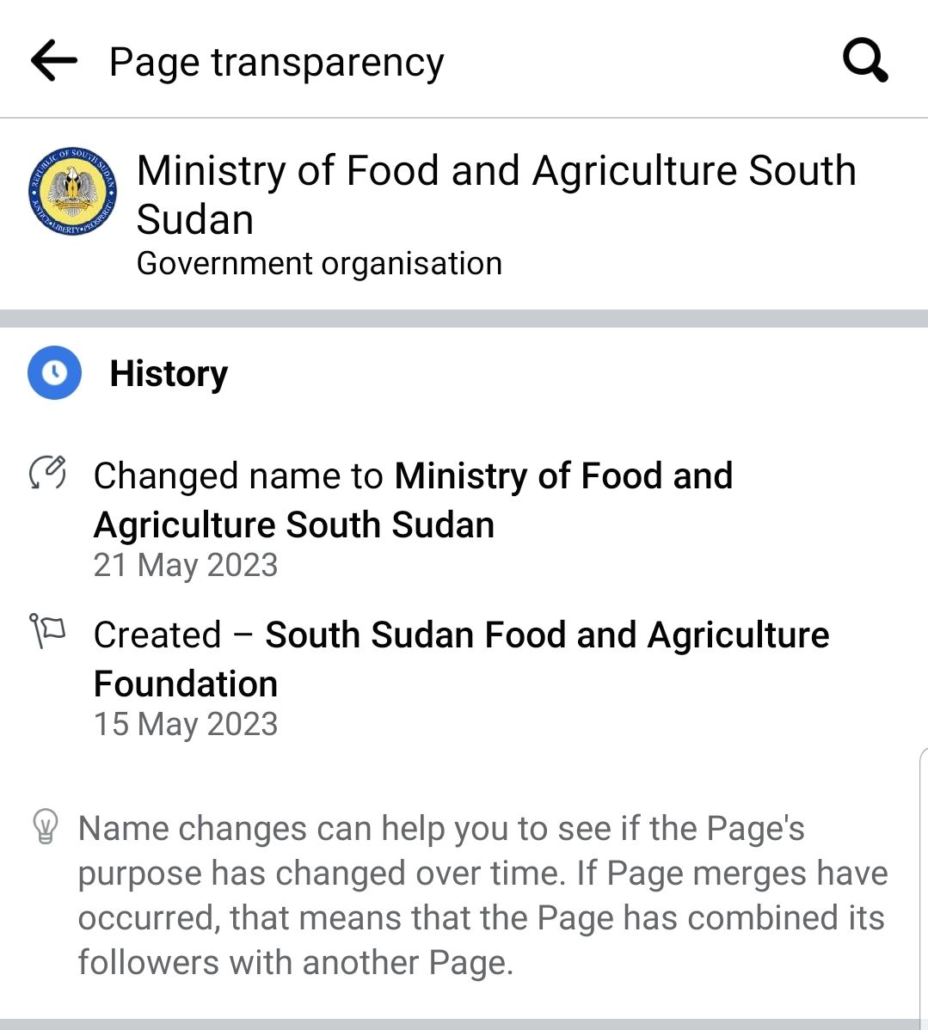

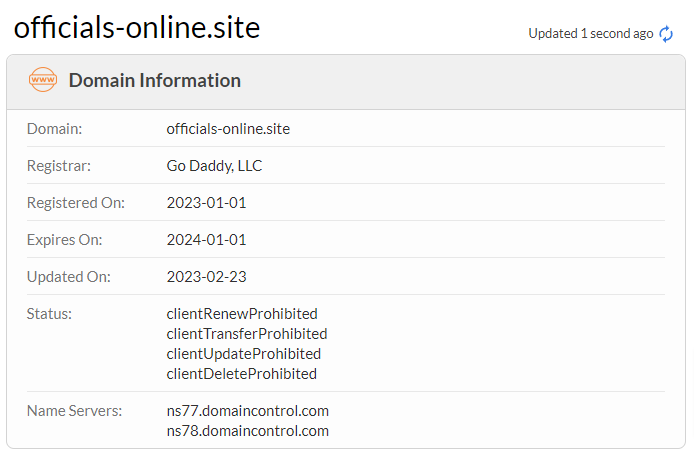

A sparse social media account

Having a believable feed on Facebook or Instagram is a little like your credit history — the further back it goes, the better it is. This is because hoping creates a brand-new persona online. They start from scratch. They’ll get around this by often putting “new account” in their profile to explain their lack of posts.

No Snapchat

For kids, one substantial red flag does not have a Snapchat account. This is because Snapchat messaging consists almost entirely of spur-of-the-moment photos and videos. Not having one means you’re probably unable to send up-to-date pics of yourself, which catfishes definitely can’t do.

Lack of online friends

Getting people to follow a fake profile can be tricky, but it’s not impossible. However, having a group of friends to comment, like, and tag you frequently on these apps is complicated. A noticeable lack of consistent peer interaction (especially for young people) is a big red flag. However, remember that a catfish could have fake, extra “friend” accounts they use to make their posts more realistic.

Talking to Your Child about Online Strangers

Often, seeing is believing — especially for kids if you ask them the question, “What is catfishing?” Our team created a video to show how easy it is for an adult to create a fake social media account and use it to start conversations with kids. Children may think they’re invincible when it comes to knowing who their friends are online, but predators can be skilled at tricking people.

Ensure you have open and ongoing conversations about online strangers and that your kids feel comfortable telling you who they talk to online. Suppose you’re worried about catfishing and need a digital safety net. In that case, Bark helps parents protect their kids from dangers like these. Alerts are sent when conversations indicate a significant age gap or potentially abusive behaviour, so you can help keep them safe online and in real life.

Below are ways to protect yourself and your personal information from potential catfish.

1. Do a background check.

You can conduct a name search or an online background check with the help of services like Information.com and Instant Checkmate. This can help reveal an individual’s social media profiles, news articles in which they could be mentioned, or other digital content containing their name. After the initial search, you can confirm further personal details like their workplace, where they come from, and their friends etc., to make sure that who they claim matches what the internet says about them.

2. Know the signs of being catfished

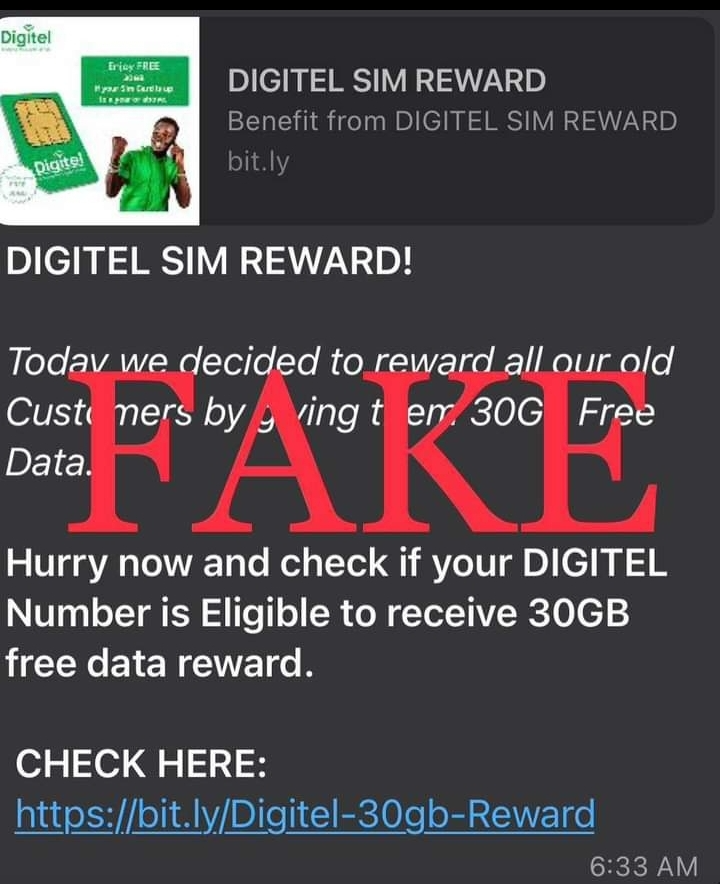

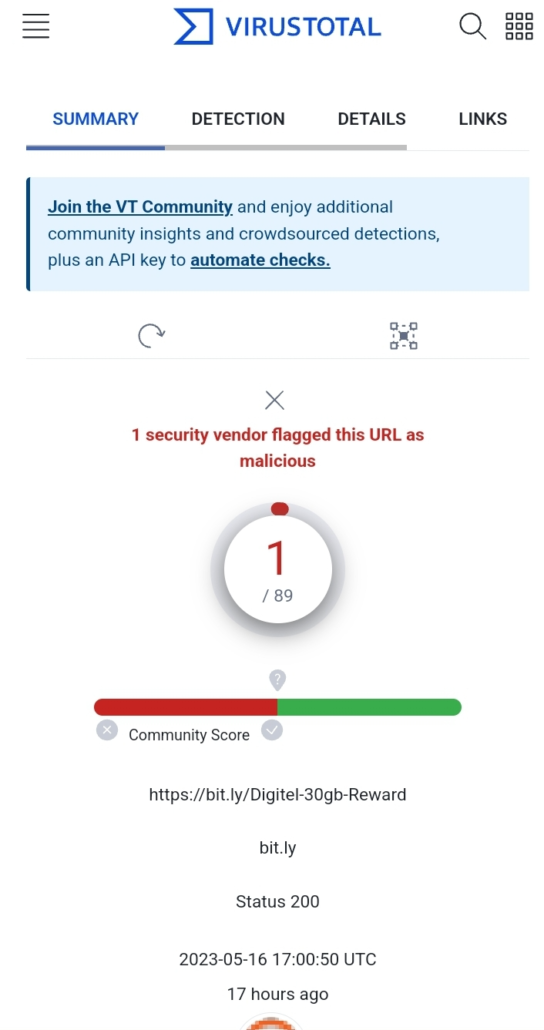

If the catfish’s description is thorough and detailed, it may be difficult to tell when you’re being caught. Since the catfish’s profile is only created to be sick, people may not have a lot of followers or friends. A catfish may never want to voice or video call, avoid in-person meet-ups, and even ask for money. These are all signs that you are being catfished and that you should put up your guard.

3. Never share your personal information.

Oversharing personal information with strangers can be dangerous. If someone you’ve just met online begins asking for your data, such as an address, additional contact information, or account details or tries to push you to tell them about your life or work, they could be catfishing you.

If they ask you for a password on the pretext of an emergency, that’s a preeminent warning sign that something is up. Asking for personal data is another big red flag because that behaviour isn’t normal and should cause alarm.

4. Be suspicious of those you don’t know.

Be careful when you receive friend requests, correspondence, or message requests from people you need to become more familiar with. Treat online conversations the same as real-life ones. While it’s okay to interact with new people and make more friends, you should be cautious and look out for catfishing signs discussed above.

5. Ask questions that require specific knowledge.

If you suspect that someone is catfishing, ask them questions that only people with their reported background would know. You can ask about malls and restaurants from where they claim to come from or something particular about what they do. Be wary of them if they’re hesitant, or try to avoid your questions.

6. Use reverse image search to identify fake profile photos.

Social media is full of fake images and profiles. If you’re suspicious of the person you’re chatting with online, consider using a reverse image search to identify fake images. This tool also allows you to confirm a photo’s authenticity by looking at similar images and the original version of the photo.

7. Try to get them into a video call.

One of the fastest ways to detect if somebody is catfishing you is to ask them for a quick video to avoid in-person meet-ups and ‘, avoid in-person meet-ups, and enter online meetings, says Caleb Riutta, Co-Founder of DUSK Digital.

Endnote

Falling into a catfishing trap can lead to financial losses, heartbreak, and misuse of peer interaction (especially for young peer interaction (especially for young people), an arch of your precious information or money.