Data Story: South Sudan Losing Battle Against Infant Mortality

As late as 2019, infant mortality rate in South Sudan remained among some of the highest in Africa.

By Charles Lotara

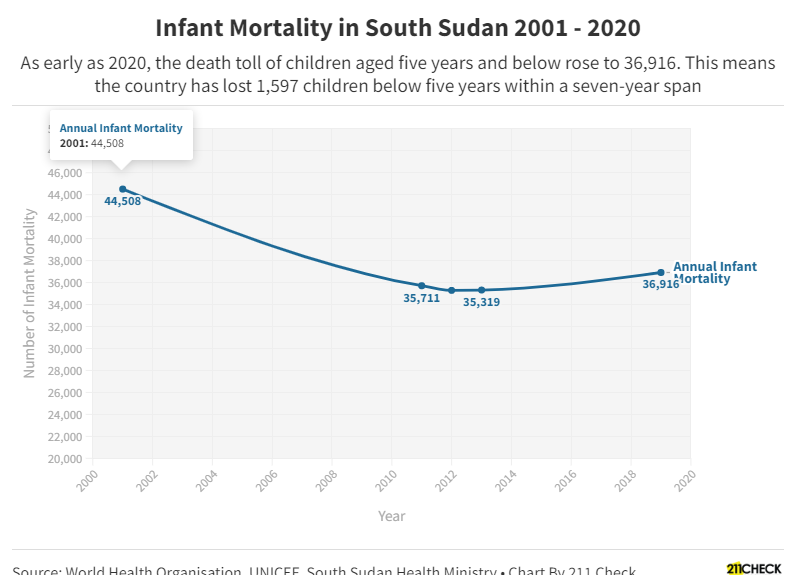

Ten years before South Sudan attained independence in 2011, the infant mortality rate was already alarming with 44,508 children dying annually before reaching age five. Boys accounted for 23,395 of this tally compared to 21,113 girls. That was as late as 2001.

This mortality ratio was attributed to inadequate midwifery services in the country. According to Global Health Workforce Alliance, a subsidiary of the World Health Organization, the ratio of midwives in the country was 1 per 38,088 populations. This was even so after the referendum.

The above factor was also compounded by the unavailability of a formal system for the supervision and support of nursing and midwifery practice in the country, especially at state level.

Similarly, at national stage, there was no legal and regulatory framework guiding midwifery practice according to a 2011 report from the Ministry of Health titled Special Supplement: Development of Nursing and Midwifery Services in South Sudan, produced in partnership with the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

But amid the above challenges, the country had made strides on mitigating infant mortality. Data from the United Nations International Children Emergency Fund (UNICEF) reveals that 35,711 and 35,288 children (boys and girls) below five died in 2011 and 2012 respectively, a sharp drop from ten years earlier.

These improvements were a result of the creation of an ambitious Health Sector Development Plan spanning from 2011 – 2016 with emphasis on Strategic Plan for Human Resources for Health (HRH).

However, the country is witnessing a stunning reversal on the achievements it has made just two years after independence thanks to a protracted civil war which weakened a nascent health system. In 2013, 35,319, an increase of 13 children under five from 2012, died.

In 2015, the World Health Organisation documented that the probability of a child dying by age five was 90.7 percent in every 1000 live births.

As late as 2019, the death toll of children aged five years and below rose to 36,916. This means the country has lost 1,597 children below five years within a seven-year span with male accounting for 852 of the total and females accounting for 588.

This alarming trend is projected to continue if no urgent action is taken according to the World Health Organization.

Mortality Rate By Year

| Year | Number of Infant Mortality |

| 2001 | 44,508 |

| 2011 | 35,711 |

| 2012 | 35,288 |

| 2013 | 35,319 |

| 2019 | 36,916 |

Efforts made

Three years after the referendum, the national Ministry of Health crafted the National Health Policy, another ambitious initiative that was to run from 2016-2026, to provide the overall vision and strategic direction for development in the health sector and also curbing maternal mortality rate.

Dubbed the NHP, the initiative was to be implemented through two five-year strategic plans: 2016 -2021 and 2021-2026. The policy – the government said at the time – draws its mandate from the Transitional Constitution, Vision 2040, the South Sudan Development Plan (SSDP), and that it was cognizant of the Sustainable Development Goals agenda.

The overall goal of the NHP was to deliver a strengthened national health system and partnerships that overcome barriers to effective delivery of the Basic Package of Health and Nutrition Services and a system that efficiently responds to quality and safety concerns of communities while protecting the people from impoverishment and social risk.

No much change

Six years later, the aforementioned initiatives have done very little to improve the health system and in particular, service delivery at the department of obstetrics and gynaecology, especially at the country’s main referral health facility, Juba Teaching Hospital.

Most health infrastructures remain dilapidated; essential medical and surgical equipment are either outdated or lacking. The management and human resource capacity has weakened.

The World Health Organisation says the Nongovernmental Organisations are still responsible for 80% of the country’s health service delivery, which complicates the coordination of service delivery.

In its Country Cooperation Agenda 2014 – 2019, the first priority of the World Health Organisation was to contribute to the reduction of maternal, newborn and child morbidity and mortality. By the year 2019, the infant mortality rate was the highest since 2011.

The World Health Organisation did very little to provide technical support for the development and implementation of policies, strategies and plans for integrated maternal, newborn, and child health.

Support for the Ministry of Health to improve the accessibility and availability of integrated maternal, newborn, and child health services at all levels of the health system has stalled and the promise to ensure accessibility and availability of emergency obstetric and newborn care within the primary health care and referral system remained unfulfilled according to a report by the Global Health Observatory.

The future looks bleak. Development assistance has remained a major source of revenue for South Sudan, especially following the outbreak of the covid-19 pandemic that sparked a sharp fall in oil prices and shrinking national revenue.

As countries around the world fret over the spread of the omicron variant, possibilities of another lockdown are imminent. This could further affect oil production and national revenue which would otherwise be used to revamp the health sector and curb the runaway infant mortality rate.

To break beyond this uncertainty, the government must utilise funding from the non-oil revenue and development assistance from the donor community and adjust the national budget for the health sector. This could significantly reduce the worrying trend of infant mortality.

Background information

Since the inception of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005, the Ministry of Health, through the Department of Reproductive Health, has been putting in place systems and mechanisms for coordinating the integration, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of Sexual and Reproductive Health services in South Sudan.

Based on data from 2006, five years before the referendum, the country had arguably the highest maternal mortality ratio in the world with 2,057 children per 100,000 live births dying before the age of five.

In 2011 and 2012, health partners, including the World Health Organisation and the United Nations Population Fund, scaled up support to the country’s health sector. This saw a significant reduction in the ratio of infant deaths.

Two years after independence, the government maintained efforts to eradicate infant deaths. It is against this background that in 2013, the Family Planning Policy was launched.

One of the aims of this policy was to provide comprehensive and integrated Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) services in line with the recommendations of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) held in Egyptian capital Cairo according to the then Minister of Health Dr. Michael Milly Hussein.

The Ministry of Health noted that one in five women of reproductive age (15-49 years) has unmet needs for spacing or limiting childbirth. This, according to the government, has also contributed tremendously to the rise in infant mortality ratio.

In December 2013, civil war broke out. This further affected the already-faltering health system and jeopardised the efforts to eradicate infant mortality rate even after the conflict.

The Family Planning Policy also provided that obstetricians give expectant mothers the necessary guidelines required to ensure safe delivery. However, this has not been implemented. Instead, obstetricians who go for months without salaries have been blamed for negligence.

As late as 2019, infant mortality rate in South Sudan remained among some of the highest in Africa. But the government is confident that the Family Planning Policy crafted eight years ago will promote an integrated approach in studies to provide insights in the development of culturally accepted and appropriate materials to be used for safe motherhood and family planning services.

About the Authors:

Charles Lotara, a Data Speaks Fellow at #defyhatenow South Sudan, wrote this data story, which was edited by 211 Check Editor Emmanuel Bida Thomas and approved for publication by Steve Topua, Data Analyst and Trainer. It’s part of the ongoing #defyhatenow South Sudan Data Speaks Fellowship program with funding from the European Union Delegation to South Sudan.

About South Sudan Data Speaks Fellowship:

This is a two-month and half data journalism fellowship for South Sudanese content creators with an aim of educating participants on the fundamentals of data journalism through in-depth training facilitated by experienced data analysts.

The fellows have been selected from across South Sudan and they are trained in data sourcing/mining, data analysis, and data visualisation for two months and half (October to Mid December)

Each fellow will produce a minimum of three (03) data stories during the fellowship. The focus will be on increasing access to information

211 Check

211 Check

211 Check

211 Check